Obtaining a decent home can be hard for people living in Chile’s isolated rural places. Housing is often poorly insulated, made from inadequate materials, lacking connection to basic services such as electricity, water and proper sanitation and overcrowding is common.

Government investment in housing and infrastructure has typically benefitted the majority (87%) of Chileans who live in towns and cities. This is why the Rural Habitability Programme was established. It provides funding and technical support to people living in rural communities of less than 5,000 inhabitants, so they can build a new house or improve their existing home.

Chile has a shortage of houses, and the Rural Habitability Programme is part of the government’s wider ‘Emergency Housing Plan’ to build more homes across the country. The programme is led by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development and carried out by its Housing Policy Division.

The programme launched in 2016 and has so far built or renovated more than 10,000 homes, improving quality of life for around 40,000 people. The target is to reach 11,298 homes by December 2025.

The project in practice

The municipality, working in collaboration with local and regional government departments identify and approach households that might qualify for the programme. Rural Management Agents (RMAs) which can be public or private bodies, are another important actor in the Programme: they also identify potential beneficiaries and guide them through the entire process, from the initial introduction through to completion of works. Other communication channels, such as radio, are also used to publicise the Programme.

Families interested in applying for funding, develop their housing ideas with the RMA and present the proposal to the Ministry, once a call for applications is open. This happens once or twice a year and can be national, regional or themed (for example, for new housing or for renovation projects).

People can apply for funding to build a new house on land they already own or to improve and extend an existing home. Communities can also group together and apply for funding for housing complexes of up to 160 homes, including the purchase of land. Extra subsidies are also available to build public facilities like community centres or sports courts.

The minimum requirement for a new home is to include two bedrooms, a kitchen, bathroom and living-dining room. Large families can add a third or fourth bedroom.

One of the standout features of this Programme is that it also allows families to build an additional ‘productive’ space to help the household generate income, sustain themselves or improve their quality of life. It might be a place to prepare fish for selling, keep food, wood or animals, a workshop for weaving, a music room or a greenhouse.

Another important aspect of the programme is that the housing is designed and delivered on a local level, respecting the characteristics of the area and its people, considering climate, geography, cultural

The Ministry assesses the applications, using a scoring system to identify the people most in need of help. Once a family has been granted funding, they must use it within 21 months. The RMA helps them to apply for any necessary permits and provides legal advice. They also help to manage the building contractors, which is often the RMA itself.

Residents can choose to carry out the work themselves. In this case, the funding covers the purchase of building materials and provides money to pay for local labour. Self-builders must attend training sessions delivered by the RMA and an external assessor is involved in supervising the build.

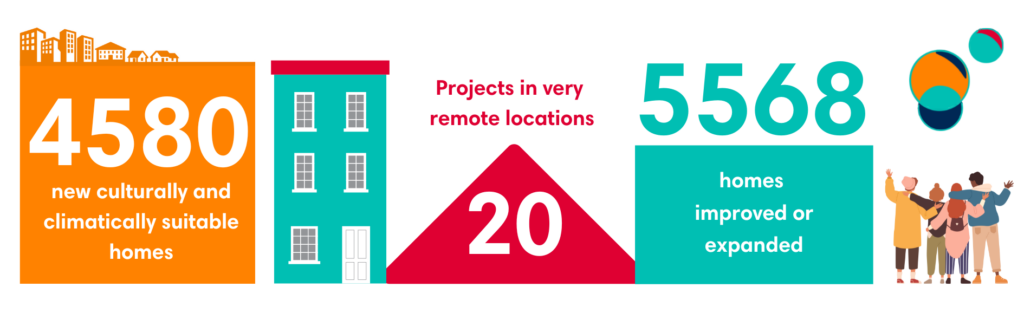

Once the construction work is finished, the building is inspected. After this, the family can move into the home. So far, 4,580 new homes have been built and 5,568 have been improved or extended.

There have been challenges along the way, including areas where it is unsafe or impractical to invest state funding because of the risk of flooding and earthquakes. Chile is very mountainous, and it can be difficult to get people and materials to extremely remote communities. To solve this problem, more subsidy is awarded to projects in very isolated locations. Additional money is also being allocated so houses can be built on Chile’s island territories: Rapa Nui (Easter Island), and the Juan Fernández Archipelago.

Social impact

One of most important aims of the programme is to reach as many people as possible across Chile’s geographically and culturally diverse regions. More than 40,000 people have already been helped, including immigrants in the north, traditional agricultural communities in the centre and south of the country, and people living in the southernmost regions of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego.

Ensuring the programme works well for indigenous people has been challenging. Some ancestral land and water rights have been returned through a Land and Water Fund, but many other basic services are lacking in these territories. In response, the Government set up the Good Living Plan, to deliver public works and welfare services for indigenous communities, to ensure that land is genuinely habitable in practice. This in turn helps the Programme to approve finance for new homes, as a funding prerequisite is connection to basic public services.

The Programme also aims to help women-led households, that historically have poorer access to State benefits. Firstly, it has made a special call for applications from this group. Secondly, it indirectly supports the development of female community leaders who often lead applications for larger housing developments of up to 160 homes. By organising and advocating for their communities they gain status, skills and empowerment, and they are also able to access other development and training opportunities from other departments connected with the Programme.

Giving vulnerable people the opportunity to live in a new or renovated home without taking on debt helps to reduce social and economic equalities across Chile. It also helps to ease overcrowding in rural homes, by allowing up to two bedrooms to be added to the base house.

Improvements to green spaces and the construction of public facilities, such as meeting rooms and workshops, benefits the wider community. Twenty of these projects are in development in extreme locations, such as the high altitudes of the Chilean Altiplano and glacial Patagonia.

Environmental impact

Climate change and environmental issues are central to the programme. Additional funds are allocated for eco-friendly improvements, such as the removal of asbestos and the installation of sanitation systems that prevent water and land contamination. Extra funding is also available for the installation of solar panels to generate free renewable energy and greenhouses to extend the growing season.

Improving the thermal efficiency of buildings keeps residents warm in winter and cool in the summer. It also lowers energy consumption and fuel costs and reduces carbon emissions. Wood-burning stoves can be fitted with a special device that uses waste gas to heat water.

Water scarcity is a major problem in Chile. The country is experiencing a ‘mega-drought’ that has lasted more than 13 years and has put huge strain on freshwater resources. The Rural Habitability Programme will include a wastewater recycling system in houses once the system has been approved by the relevant authorities.

Funding

The programme is funded by Chile’s national government. In 2023, the annual budget for the programme was $126,854,338,000 CLP ($159,202,194 USD). This is 6% of the total budget for the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development.

The average amount of funding to build a home is $49,840,000 CLP ($62,500 USD). The cost of construction is covered by different components: the basic subsidy; additional subsidies; contributions from third parties (such as regional government), and varying levels of personal contributions depending on financial capacity.

The total amount of finance depends on the size and composition of the household, level of education, income and isolation, among other factors. There is no limit on the maximum income per household, but the most vulnerable families are given priority and are awarded more money. People over 60 years old, living in the most isolated areas and those within lowest 40% income bracket are given the highest priority, and often do not pay anything for a new home. Households within the 41% to 60% income bracket contribute around $357,000 CLP ($450 USD) towards the cost of their home.

Transfer and expansion

The Chilean government believes the Rural Habitability Programme can be replicated internationally and officials responsible for the programme have attended forums dedicated to sustainable development in Latin America and the Caribbean.

At home, the programme is exploring the use of prefabricated materials. It is hoped that using pre-made elements (which are then transported to site for assembly) will further improve the quality of the homes, reduce the cost of getting materials to site and construction time.

It is unusual for a government to focus on rural, rather than urban, communities as part of the solution to a national housing shortage. The Rural Habitability Programme highlights the responsibility of the state to all its citizens, no matter where they live, and gives people in challenging circumstances the chance to have a decent home without the need to leave their community or way of life.

Download your free copy of the full project summary

Amidst the green fields of Nuevo Imperial, a remote corner of Chile’s Auracania region, reside Arturo and Carmen, a couple in their eighties whose lives were changed when they were accepted to receive a grant from the Rural Habitability Programme.

Amidst the green fields of Nuevo Imperial, a remote corner of Chile’s Auracania region, reside Arturo and Carmen, a couple in their eighties whose lives were changed when they were accepted to receive a grant from the Rural Habitability Programme.