Like many major cities across the world, Jakarta is home to numerous informal settlements, where thousands of low-income families have made their homes and set up businesses. The settlements are known as kampungs in Indonesia and often occupy prime land with potential for commercial development. For decades, politicians portrayed the kampungs as a serious barrier to the creation of a modern, well-planned and sanitary Jakarta. This narrative proved popular with voters and meant kampung residents lived in fear of forced eviction.

These fears became reality for more than 10,000 families who were forced to leave their homes between 2015-2016. Flood management, road construction, urban planning, and illegal land occupation were among the reasons the city government gave for the mass evictions, which were largely backed by the public.

Faced with homelessness, kampung residents began working with organisations operating in Jakarta’s low-income neighbourhoods to challenge forced evictions and other housing injustices. Together, they set up a community-centred project to push for legal and political changes that would give residents the right to stay in their neighbourhoods and improve their living conditions.

The project – Housing Rights in Jakarta: Collective Action and Policy Advocacy – initially focused on two eviction cases in four kampungs across the city: Kampung Akuarium in the Kota Tua heritage area, and the riverbank kampungs of Tongkol, Lodan and Kerapu.

Through a mixture of community collaboration, political advocacy and network development, the project successfully stopped the eviction of 256 people in the riverbank kampungs, and helped 400 families, who had already been evicted from Kampung Akuarium, return to the area to live in newly constructed housing. In addition to this, the project challenged negative public perceptions of informal settlements and achieved city-wide regulatory changes that protect all kampung residents from forced evictions.

The project in practice

The project is run by three organisations: Jakarta Urban Poor Network (which represents residents of 25 kampungs); Rujak Centre for Urban Studies (a think-tank focusing on urban issues); and Urban Poor Consortium (a networking and advocacy organisation). Other organisations provide legal and technical support when needed.

The city government argued that proposed evictions in the riverbank kampungs were necessary to improve flood management, public order and spatial planning. So, project organisers worked with residents to see if homes could be altered in a way that would solve these issues and allow them to stay.

A residents’ association was formed – Komunitas Anak Kali Ciliwung (KAKC) – and a series of community meetings and negotiations with the city authority were held. The decision was made to move the homes five metres away from the river’s edge so the government could build an inspection road. Trees were planted along the riverbank to prevent landslides and a stronger, higher embankment was built to reduce the risk of flooding.

Septic tanks were installed in the homes to stop sewage entering the river and small gardens were added to the front of each house. KAKC contacted the University of Indonesia to teach residents how to manage waste, grow vegetables and maintain a healthy living environment. This meant residents could be seen as the guardians of the riverbank, rather than the source of environmental problems.

The situation was different in Kampung Akuarium. The city government said it wanted to revitalise the Kota Tua heritage area and that the kampung was illegal. It had already evicted 400 families and cleared the land, but some residents had returned and were living in worse conditions than before. The project helped them submit a lawsuit against the authority, citing inappropriate eviction procedures.

A year after the eviction, the project arranged a ‘political contract’ with one of the candidates for Governor of Jakarta. The communities represented by Jakarta Urban Poor Network agreed to support him in the 2017 election on the condition that he would retract kampung evictions and protect the community’s residency rights once in power.

This groundbreaking alliance was the starting point for political engagement with kampung residents and led to important policy and regulatory changes. These included urban planning for kampungs, land legalisation and financial support for improvements, and the construction of five new housing blocks at Kampung Akuarium.

In 2019, the project helped Kampung Akuarium’s residents to form a housing cooperative. As a legal organisation the cooperative was able to negotiate with the developer to shape the design of the new apartment blocks and take on the management of the buildings. It has also signed an agreement with the city government which will transfer ownership of the building to the cooperative in the future.

Members of the cooperative were trained to supervise construction and carry out maintenance work. Two apartment blocks have been completed (104 units) so far and the remaining three are under construction (137 units). The cooperative has a gardening team and a group that manages a variety of on-site income-generating activities, including a laundry, homestay and catering business.

Social impact

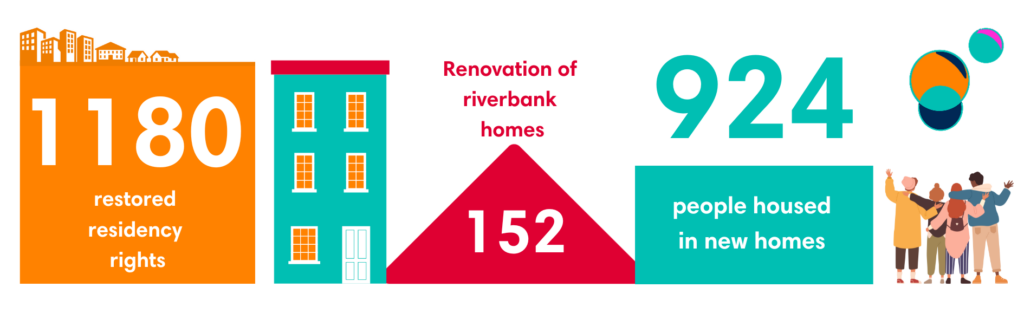

This project is the first of its kind in Indonesia and has maintained or restored residency rights for 1,180 kampung residents. More than 900 people will be rehoused in the new apartment buildings in Kampung Akuarium, and 152 homes were renovated in the riverbank kampungs.

The project’s pact with the new governor led to policy and regulatory changes which have benefitted thousands of residents of other kampungs across Jakarta. These included a government programme to channel funds into neighbourhood improvements and another to include residents in these processes. The project further strengthened community involvement by establishing several kampung residents’ associations and cooperatives.

Other regulatory changes include the reclassification of existing kampungs as legal settlements and the issuing of building permission certificates for 9,706 houses in 32 kampungs. The project is ongoing and hopes to secure building permits and re-classification changes for 5,000 kampung households.

Environmental impact

The risk of land slides and flooding has been reduced in the riverbank kampungs, while pollution has decreased thanks to the addition of septic tanks and improved household waste management.

The new apartment blocks at Kampung Akuarium comply with building regulations, which stipulate a 50:50 ratio of buildings to green areas. There is a communal garden with a pond and a new drainage system which connects to the city’s canals. Residents manage their own organic waste collection and processing.

The design of apartments was influenced by residents and is very different to government-owned public housing. Every room has good air circulation without the need for artificial ventilation, like electric fans and air conditioning.

Funding

The project is primarily funded by Rujak Centre for Urban Studies (which is supported by a variety of international foundations), the government, universities and the kampung residents themselves.

In Kampung Akuarium 1,322,631,975 IDR ($88,900 USD) was spent on co-design workshops and temporary shelters. Rujak Centre for Urban studies spent 3,570,660,000 IDR ($240,000 USD) on technical expertise and architectural services and the developer paid an infrastructure levy of 148,236,922,320 IDR ($10,000,000 USD). Kyoto University, Toyota Foundation and the Japan Foundation spent 163,606,661 IDR ($10,994 USD) on developing the community’s skills.

Residents pay 240,000 IDR ($16 USD) per month to the cooperative. This is a lot cheaper than rent for public housing, which is at least 750,000 IDR ($41 USD) per month. Some of this contribution pays for the operation and maintenance of the buildings and some goes into a sinking fund. Apartments cannot be rented or sold outside the cooperative structure.

Residents of the riverbank kampungs raised 2,032,380,000 IDR ($137,168 USD) towards the cost of housing renovations and infrastructure improvements. The government gave a grant of 50,000,000,000 IDR ($3,374,471 USD) and additional funding came from the Latin American, African and Asian Social Housing Service (210,000,000 IDR / $14,170 USD) and the University of Indonesia (100,000,000 IDR / $6,746 USD).

Home improvements were paid for by homeowner contributions and loans from a revolving community fund set up by the residents’ association.

Transfer and expansion

In the short term, the project plans to complete construction of the remaining apartment blocks at Kampung Akuarium and finalise the donation of the building to the cooperative. It also hopes to settle the legal status of the riverbank kampung lands to secure the community’s right to live there.

The project’s approach has already been scaled up to other kampungs in Jakarta and there is strong interest from Indonesia Urban Poor Network to replicate it both regionally and nationally.

What began as a localised effort to help residents push back against forced evictions in four kampungs has grown to have far-reaching benefits for thousands of people living in informal settlements across Jakarta and possibly the whole country. Despite a long history of mass evictions, many kampung residents now have the right to live on the land they occupy in improved conditions, while others have reason to be hopeful about their future.

Download your free copy of the full project summary

Like many major cities across the world, Jakarta is home to numerous informal settlements, where thousands of low-income families have made their homes and set up businesses. The settlements, known as ‘kampungs’ in Indonesia, often occupy prime land with potential for commercial development. For decades, politicians portrayed the kampungs as a serious barrier to the creation of a modern, well-planned and clean Jakarta. This narrative proved popular with voters and meant kampung residents lived in fear of forced eviction.

Like many major cities across the world, Jakarta is home to numerous informal settlements, where thousands of low-income families have made their homes and set up businesses. The settlements, known as ‘kampungs’ in Indonesia, often occupy prime land with potential for commercial development. For decades, politicians portrayed the kampungs as a serious barrier to the creation of a modern, well-planned and clean Jakarta. This narrative proved popular with voters and meant kampung residents lived in fear of forced eviction.

Yani, her family, and 40 other families lived in rubble after Akuarium village experienced forced eviction on April 11, 2016. Residents lived in rubble for almost two years without water and electricity sources and among harsh coastal weather.

Yani, her family, and 40 other families lived in rubble after Akuarium village experienced forced eviction on April 11, 2016. Residents lived in rubble for almost two years without water and electricity sources and among harsh coastal weather.