Pierre Arnold and Nina Quintas are project managers at urbaMonde, a French-Swiss organisation that promotes Community-led Housing (CLH), by providing technical support to projects and residents and through the co-ordination of the CoHabitat Network.

The COVID-19 era brought important changes in the way we live, work and socialise. Living in adequate housing is critical to be able to face and adapt to this crisis. The CoHabitat Network promotes Community-led Housing (CLH) as a transformative non-speculative way to conceive, manage and protect our living environment. During the pandemic, We Effect put urbaMonde in charge of conducting a global study to assess whether CLH initiatives offer comparative benefits to their residents to collectively resist the health, social and economic impacts of the crisis.

Between September and October 2020, the global survey received 1,047 responses from 72 countries and Caribbean islands, from residents with a wide variety of housing tenure: Collective Land Ownership (Community Land Trusts, housing co-operatives), individual property (fully paid or being paid), rental housing (public or private), borrowed housing (generally informally rented) and irregular land occupation (generally informal settlements). In the survey, Community-Led Housing is mainly represented by Collective Land Ownership (CLO) initiatives, as well as a few co-housing initiatives and organised informal settlements, where the community is at the centre of the decision making about the conception, modification and/or management of their built environment. The study also included 52 follow-up interviews.

One of the main results of the study points to stronger levels of security of tenure when land is collectively owned/managed. In fact, during the pandemic, CLH initiatives show a higher protection against eviction and foreclosure processes than other housing types.

Eviction threats amid the pandemic

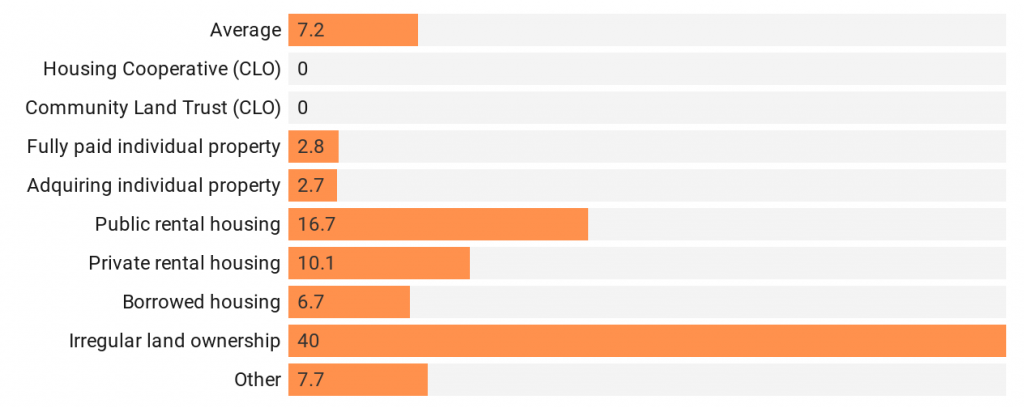

As the following figures show, respondents from housing co-operatives and Community Land Trusts haven’t been threatened with evictions since the beginning of the pandemic. In contrast, there are high percentages of such threats amongst respondents with other types of tenure, especially in irregular land ownership (40%), and public and private rental housing (16.7% and 10.1%).

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents by land occupancy status who received threats of eviction since the beginning of the pandemic.

Forced evictions are known to make households extremely vulnerable and in many cases constitute a violation of several human rights. In the context of the pandemic – this is aggravated by the fact that not having a home greatly increases COVID-19 related health risks for evicted households, but also the surrounding communities.

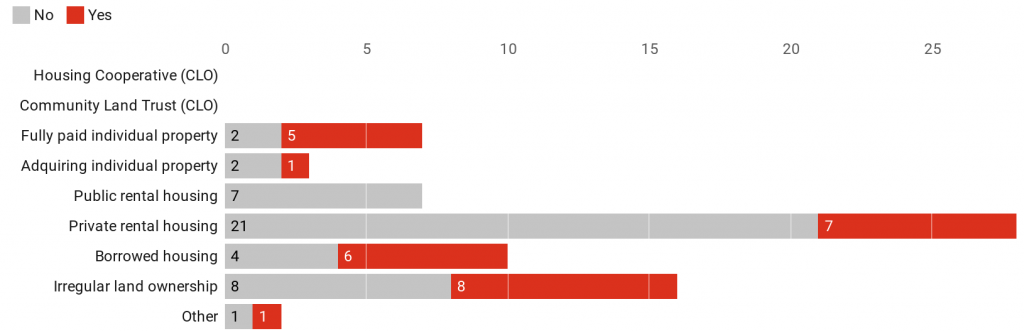

Among the 73 respondents who had been threatened with eviction since the beginning of the pandemic, 28 (21 women and 7 men) declared that they have indeed been evicted (in Bangladesh, India, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Brazil, El Salvador, Nicaragua Kenya, Nigeria and Zimbabwe). Those evictions can be individual (a formal or informal tenant being evicted by a landlord, or foreclosure for a household buying a private property), but also collective (part of an informal settlement being removed by a public authority for an infrastructure or tourist project for instance).

Figure 2. Effective eviction of respondents who had been threatened during the pandemic, by land occupation status.

How does Community-Led Housing prevent the risk of eviction?

In many of the 52 follow-up interviews, land tenure security has been highlighted as one of the main advantages of housing co-operatives, Community Land Trusts and co-housing initiatives. Those examples show how security of tenure is achieved by CLH initiatives in different countries.

Mutual-Aid Housing Co-operatives (MAHC) in Latin America usually create a ‘relief fund’ or ‘solidarity fund’ to which co-op members make monthly contributions in addition to their mortgage repayment to the co-operative. “The relief fund was essential during the pandemic to make sure we feel safe and that we’ll be able to stay in our homes” explained Iris from the 13 de Enero MAHC in El Salvador. Each one of the 34 households of her co-op made a monthly contribution to the relief fund during the first year after moving in, gathering around 7,700 US dollars. Those collective savings, to help co-op members facing economic difficulties, have proven to be very useful during the pandemic, especially for households who could not generate incomes and did not receive support from public schemes.

In other types of cooperatives and co-housing schemes, including the Abricoop housing co-operative in Toulouse, France, monthly loan repayments are proportional to each household’s incomes from the previous year. Such a mechanism does not help reduce housing costs instantaneously, but it can at least allow households who lost part of their incomes in 2020 to have lower repayment rates in 2021, facilitating their economic recovery. Similarly, in Milton Park housing co-operative in Montreal, Canada “the rent is affordable and you have back up and resources from the community”, explains Pascale who is a tenant of the co-op and who lost more than half of her usual income since the beginning of the pandemic.

Community Land Trusts have also shown a strong resilience to economic recessions, including during the subprime crisis in 2008-2010 in the United States. This also seems to be the case during the current COVID-19 economic crisis. Private rental tenants, co-operative tenants and homeowners on the land stewarded by CLTs have lower housing costs than on the free market. Moreover, for those who have difficulties paying back mortgages, the CLT can help with negotiating with the banks. When there is no other option, CLTs can buy the houses from the households before they would go through foreclosure, and help them find an adequate rental home, within or outside the CLT, as explained in interviews given by the CEOs of Champlain Housing Trust in Vermont, and Dudley Neighbors Inc. CLT in Boston, Massachusetts.

Generally, CLH also increases the capacity to collectively negotiate a repayment adjustment with the financial institution (payment deferral or reduction, interest rate reduction, etc.), or to get assistance from public housing institutions or local authorities.

“Without the collective property, a bank would have already evicted us for not being up to date with the monthly payments, but here no-one is going to take us away from our house” says Silvia from the Fe y Esperanza MAHC in Guatemala.

Similarly, Damaris from Altos del Sureste MAHC in León, Nicaragua stresses “I feel at ease, [we] have the support from the Central of Co-operatives as well as We Effect”.

Many other testimonials received in the survey and interviews show that in places where a strong sense of community existed before the pandemic, neighbours could help each other and also organise in solidarity with vulnerable groups in the local community, the city or even at national level. Nevertheless, as the economic crisis extends and deepens, and the possibilities of generating income are increasingly limited, even some CLH initiatives may not be able to guarantee the security of land tenure for future years, especially in countries where State responses and protection mechanisms are scarce or non-existent.

A new survey in one or two years’ time could reveal whether CLH initiatives started showing difficulties or not, but for now they have proven to provide powerful mechanisms to keep residents safer against several negative impacts in times of unprecedented difficulty. Therefore, CLH initiatives should be promoted by local, regional and national governments to foster more resilient and cohesive societies, capable not only of facing different challenges, but also able to provide affordable housing for several vulnerable groups, from low-income and informal workers to elderly and single-parent households.

Find the whole study here: Community-Led Housing in the COVID-19 context.

Image: Alpas Homes, San José del Monte Bulacan, Philippines

Join the discussion