A government run initiative, this programme works with the private sector to provide stand alone solar energy systems to homes in remote rural areas. Improved lighting reduces kerosene and pinewood use and improves air quality and health. It allows children to study at home and gives flexibility in working time. The partnership has installed 41,379 home systems to date at a cost of US$ 133 per house and provides maintenance and installation training to rural people.

Project Description

Aims and Objectives

- To improve the living conditions of the rural population by increasing access to rural energy solutions that are efficient, versatile and environmentally responsible.

- To establish a national framework for the dissemination of quality solar energy systems.

- To increase affordability and access to solar energy systems for the rural poor.

Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world, with approximately 38 per cent of its population living below the poverty line. The average annual income per capita is around $270 and around 80 per cent of the population depends on agriculture, which accounts for only 40 per cent of the country’s GDP. A typical Nepalese home has two to four rooms, depending on family size, house type and economic conditions. Most homes are made of stones and clay, with roofing made of straw thatch or clay tiles. Eighty-five per cent of the population living in rural areas have very little or no infrastructure. Light is typically provided by one or two kerosene wick lamps, except in the high mountain regions, where kerosene is too expensive and not easily available and the usual means of lighting is burning pinewood. Such lighting systems not only provide poor lighting but also generate smoke that affects the families’ health and has global environmental implications in terms of CO2 emissions and the depletion of natural resources.

A five-year Energy Sector Assistance Programme (ESAP) was launched by the Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC) in 1999 with support from the international donor agency Danida. The AEPC is a national governmental organisation that was established in 1996 under the Ministry of Science and Technology to promote alternative energy solutions. The main activities of the organisation include the Solar Energy Support Programme, Mini-grid Support Programme, Improved Cooking Stove and the Kanchanpur-Kailali Rural Electrification Project. Besides ESAP, the AEPC has a number of other rural energy programmes, funded by various donors, including a Biogas Support Programme, Rural Energy Development Programme, the SNV-supported Improved Water Mill Programme and a Renewable Energy Programme on solar PV and solar thermal systems, which is funded by the European Commission.

The Solar Energy Support Programme is a demand-driven integrated national programme, where private solar companies supply individually owned Solar Home Systems (SHS) on a commercial basis with government subsidy of 20 – 50 per cent, depending upon the location and size of the systems. The SHS, which are used primarily for lighting purposes, are installed in remote areas outside the reach of the main electricity grid or of mini grids from micro-hydro power plants. They are stand-alone solar energy systems that provide enough electricity for around two to four bulbs. Many households use the electricity for other purposes as well, such as the operation of radios, TVs and other appliances. To date, over 43,000 SHS have been installed and the programme has reached 72 out of 75 districts and around 1,650 out of the approximately 2,000 Village Development Committees (VDCs) without access to electricity in the country.

The first stage of the programme, which was completed in September 2004, was primarily concerned with promoting the SHS, building capacity among private sector solar companies, setting up a national network of suppliers and monitoring the SHS in the field. The second stage of the programme will focus upon increasing access and affordability for a larger segment of the rural poor through the development of appropriate micro-credit mechanisms.

The main SHS components are imported from South and East Asia and assembled in Nepal and very few are manufactured by the qualified local companies. Private solar companies are responsible for marketing, installation, maintenance and after-sale services. A number of governmental and non-governmental organisations such as the Solar Energy Test Station (SETS) are involved in quality assurance and monitoring activities.

For the 43,647 SHS installed, capital subsidy amounted to $4.9 million, of which 90 per cent was borne by Danida and 10 per cent by the government of Nepal. The total budget for running the first stage of the programme, which ended in September 2004, was around $860,000 and was funded by Danida. Around five per cent of this amount was contributed by the government of Nepal through office facilities and staff. Besides the direct subsidy and technical assistance, the government provides a fiscal incentive to solar companies by waiving VAT and import tax on components imported for manufacturing and assembling the SHS.

The cost to the user for an individual SHS is around $350 for an average system and $140 for a small 12 Wp system. Danida is continuing to support the programme and Norad also began to provide financial support from October 2004. In the event of a funding deficit, the programme will seek other donors; however the ratio of funding from donors (90 per cent) and the government of Nepal (10 per cent) will remain the same.

Users are not involved in the planning and design of the Solar Home Systems but are free to choose the supplier as well as the system size and configuration that is appropriate to their requirements and budget. Once installed, users are entirely responsible for the care and maintenance of the system, except for those aspects covered by the supplier’s warranty and the two mandatory after sale service visits by the supplier.

The greatest impact of the SHS on the local community has been the improvement in children’s education, as improved lighting has allowed children to study more at home. Other impacts, which have been identified by users’ surveys and anecdotal reports, include improved access to entertainment and information through the radio and TV; improvements in health as a result of improved quality of air and light; enhanced interaction among family and community members; increased opportunity for income-generating activities and flexibility in working time, particularly for women; and improved skills for young people through training and employment.

The reduced use of kerosene and pinewood results in improvements to the local as well as the global environment. A reduction in the need for foreign currency to import kerosene has reduced the burden on the national government and improved trade balance.

The ESAP has been instrumental in the formulation of government policy on rural renewable energy promotion. The existing subsidy policy, after three years of its implementation, is currently being reviewed to incorporate new elements that are deemed necessary based upon the SSP experience.

Why is it innovative?

- Quality assurance mechanisms such as the after-sales service visits and user feedback reports act as a way of monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of the SHS in the field.

- The sectoral support approach inherently leaves room for continuous innovation in the programme.

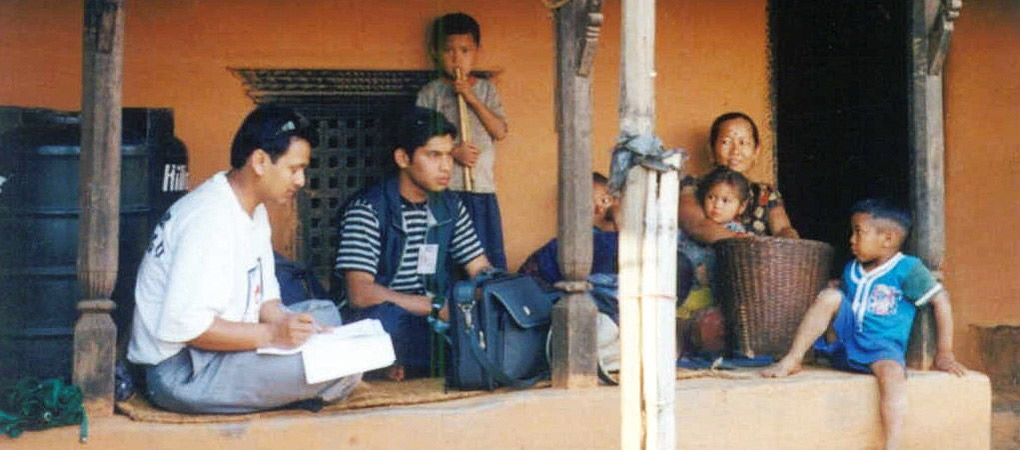

- The project relies on a unique public-private partnership, where a government agency has formed a partnership with existing organisations in the private sector. This not only reduces cost but also increases sustainability and expands ownership and responsibility.

- By the end of Phase I (September 2004), over 43,000 rural households were electrified through SHS. This is 72 per cent higher than the target of 25,000 households.

- Over 300 branch offices or dealers are now spread throughout the country, as companies have expanded their rural network to all villages where there is no electrical grid or mini-grid.

- The project has trained over 1,400 rural people as technicians or salespersons for solar companies.

- One year after installation, 94 per cent of the SHS are working without serious problems. The remaining 6 per cent can be repaired at a low cost; there is difficulty, however, in communication between the users and the suppliers, mainly due to the difficult security situation in the country.

What is the environmental impact?

The SHS uses solar power to provide energy to households in remote rural areas without access to electricity and ensuring a more appropriate use of energy is one of the key features of the programme. An average of 4.48 litres of kerosene per month per household is saved through the installation of SHS. This amount of kerosene burned in 20 years (the estimated lifetime of SHS) translates to around 3 tonnes of CO2 emissions per household going up into the atmosphere.

In high mountain regions, a household burns an average of 1.47 kg of pinewood per month, which translates to around 353 kg of pinewood over a 20-year period. The use of solar energy as a substitute for the burning of pinewood for lighting purposes not only reduces indoor pollution and CO2 emissions but also contributes toward the conservation of natural resources, considering the slow growth of pinewood in mountainous areas.

Is it financially sustainable?

The second stage of the SSP aims to address issues of social justice and improved access and affordability for poor rural households. ESAP plans to expand its international partnerships and become a multi-donor funded government programme. However, as the programme relies on international donors for 90 per cent of its funding, there is some concern over the possibility of a delay to the implementation of the second stage due to current political developments in Nepal and the resulting reservations of the international community.

As a part of the programme, over 700 rural people have been trained as technicians for the 15 qualified solar companies throughout Nepal. To date, around 690 people have been certified as Solar Electric Level 1 Technicians, who are qualified for installation and after-sales services. Most of these certified technicians are still active in the profession and most are from areas where SHS are being installed. The programme has also generated employment for 700 rural salespeople. Whilst user surveys have reported increased opportunity for income-generating activities for households as a result of the programme, to date there has been limited incidence of actual income generation after the installation of SHS.

Whilst Solar Home Systems are still not affordable for many poor rural households. Once appropriate credit mechanisms have been made available, the amount saved on kerosene and dry cell after the purchase of SHS (an average of NRs 146 per month) could easily finance the purchase of SHS over an 8-year repayment period.

What is the social impact?

The second stage of the programme aims to develop and test an appropriate modality to promote larger photo-voltaic systems meant for institutional and community facilities such as schools, health centres, community centres etc.

Rural people have been trained as technicians for the solar companies involved in the programme and provide installation and maintenance services. The ability to operate radios and TVs has increased access to information for rural households.

The programme has contributed toward significant improvements in health through reductions to indoor pollution. A World Bank study has revealed that a house with kerosene as the lighting source results in indoor air pollution equivalent to smoking two packs of cigarettes a day for exposed occupants. The indoor pollution problem that still remains as a result of the burning of firewood for cooking and heating purposes is being addressed by the Improved Cooking Stove Programme within the ESAP.

Barriers

- Difficulty experienced in addressing wider development issues such as poverty and gender. The programme is planning to link up with other rural development programmes to create synergy in addressing these issues.

- SHS are relatively high-tech, with electronic components that are prone to fail, and the repair service is not easily available in rural Nepal. The strategy to address this problem has been for solar companies to train and employ local people as technicians, who are skills tested and certified by another government body.

- Working with the private sector, where rural residents do not have control over the solar companies, can lead to corruption and manipulation. Strict penalty systems have been put into place and the programme is continually working to improve its criteria and mechanisms for quality assurance and monitoring so as to discourage any misconduct.

- The poorer sector of the rural population still finds it difficult to purchase an SHS. The programme is taking steps to develop and promote an appropriate credit mechanism to increase accessibility for the rural poor.

- The integrated nature of the programme and the relationship amongst state organisations and private sector companies and the difficulties in reaching the poorest sections of the community are possible future barriers which must be overcome for the successful transfer of the project.

Lessons Learned

- Lighting houses with SHS is sustainable but very challenging when implemented with a demand-driven and private sector led approach; it is also difficult to plan resources under such conditions.

- Working in partnership with the private sector and other relevant stakeholders helps to ensure the sustainability of the programme, as a broader range of groups take ownership of the initiative.

- Working with the private sector enables service delivery to rural people even when the state finds it too difficult to operate because of the insurgency.

- The private sector is efficient and quick to expand its network to remote areas of the country. However, despite repeated orientation and corrective actions, there has been a clear emphasis on quantity rather than quality.

Evaluation

Whilst a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation system is still in its development stage, a number of monitoring mechanisms are currently in place. These include an annual quality assurance and monitoring process that is carried out based on random sampling of the SHS installed every year, giving information on the current situation on the ground and also providing feedback for companies’ performance evaluation and grading; an integrated MIS to manage the information; and periodical surveys and impact studies that are carried out to provide information and feedback to the programme and its partners.

Transfer

The programme has reached 72 out of 75 districts and around 1,650 out of the approximately 2,000 VDCs without access to electricity in the country.

Although there has been limited adaptation of the SSP within existing national rural energy projects and programmes to date, there is strong potential for transfer and the upcoming EU funded Renewable Energy Project is planning to replicate or adapt a number of aspects of the Solar Energy Support Programme.

A solar PV project in Burkina Faso, also funded by the Danish agency Danida, is adapting the SSP methodology for quality control of photo-voltaic components.

Partnership

National Government, Donor Agency, NGO